by Steve Haner

First published this morning by the Thomas Jefferson Institute for Public Policy.

Rejecting an agreement that its own staff reached with Dominion Energy Virginia, the State Corporation Commission has imposed at least some level of financial risk on the utility’s shareholders should its $10 billion offshore wind project fail to match the company’s promised performance.

Lest you think that means the ratepayers can relax, the long final order issued August 5 once again highlights all the things that could go wrong with the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW) project, scheduled to be fully operational by 2027. The regulators also wash their hands of any responsibility and record for posterity that the Virginia General Assembly made them approve this.

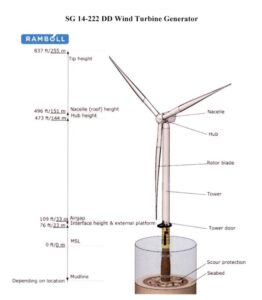

The project, which still faces federal reviews, but which is beloved of the Biden Administration, calls for 176 turbines and three substations to be constructed 27 miles off Virginia Beach. Generated electricity will then come ashore, and 17 miles of major transmission upgrades will be built to feed it into the grid. The nameplate value is almost 2,600 megawatts; but that is misleading, as the company is only promising a 42% capacity factor – fewer than 1,100 megawatts of average output over time.

As previously discussed, several parties to the case urged the commission to convert that promised 42% capacity factor into a firm commitment, with possible financial penalties. The idea was fleshed out by an expert witness retained by Attorney General Jason Miyares (R), who cited a previous Virginia case where a performance requirement was imposed on a Dominion solar deal and similar agreements in other states dealing with onshore wind.

Miyares and other parties, including environmental advocates otherwise very supportive of wind energy, refused to join a stipulation between Dominion and the SCC’s own technical staff in part because it lacked such a performance agreement. Before abandoning the idea in the stipulation, the staff had also called for a performance agreement, but at a much lower (and easier to meet) 37% capacity factor.

The Commission’s rejection of that stipulation is the secondary headline here. It also ignored the staff’s stipulation and imposed more stringent notice requirements – 30 days – if the utility faces construction or other problems that are going to raise the ultimate cost to consumers.

In its own media release on the decision, Dominion noted it is evaluating the performance agreement and that the order “does not outline the details surrounding that requirement.” Everybody is being very cagey so far, but a motion for reconsideration might follow, and the utility has a right to appeal to the Supreme Court of Virginia.

Here is what the order does say about the performance standard:

Specifically, beginning with commercial operation and extending for the life of the Project, customers shall be held harmless for any shortfall in energy production below an annual net capacity factor of 42%, as measured on a three-year rolling average. As noted by the parties requesting such, this performance standard does not prevent the Company from collecting its reasonably and prudently incurred costs. Rather, it protects consumers from the risk of additional costs for procuring replacement energy if the average 42% net capacity factor upon which the Company bases this Project is not met.

Dominion, nonetheless, asserts that it would be inappropriate for the Company to be put at risk if it fails to meet the capacity factor upon which it has justified and supported this Project. We disagree.

“Additional costs for procuring replacement energy” is the operative phrase. If a few years from now the facility is operating at 35-40% capacity, and the rest of Dominion’s system is chugging along, there likely will not be substantial “additional costs,” if any. On the other hand, a catastrophic failure bringing a three-year period down to minimal or no output, and Dominion could be on the regional market buying quite a bit of very expensive “replacement energy.”

Before this does much good for consumers, there will be more courtroom disputes, more high-fee expert accountants and witnesses and tap dancing lawyers, and even appeals. This never gets simpler.

The decision creates yet another stand-alone rate adjustment clause on Dominion bills, this one to be Rider OSW. It should appear in September and start to grow in the next few years, peaking at more than $14 per 1,000 kilowatt hours of usage in 2027. Then it tapers off but remains for decades. Many moving and unpredictable parts will determine the future charge to customers, as discussed here.

Assuming it qualifies for massive federal tax credits, only a portion (about $7.4 billion) of the initial capital cost will be paid by customers. However the order warns:

To be clear, total Project costs, including financing costs, less investment tax credits, are estimated to be approximately $21.5 billion on a Virginia-jurisdictional basis, assuming such costs are reasonable and prudent. And all of these costs, not just $7.38 billion, will find their way into ratepayers’ electric bills in some manner. [Emphasis added.]

Only two of the three seats on the Commission are filled, by former Virginia Attorney General Judith Jagdmann and former Federal Energy Regulatory Commission staffer Jehmal Hudson. As she has done before, Judge Jagdmann added her own thoughts in a concurrence, focusing again on how the Commission’s hands were tied by the General Assembly’s actions. Beginning on page 40 of the order she wrote:

…the statute clearly establishes that this Project represents the will of the General Assembly. Almost four years ago, this Commission approved Dominion’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind demonstration project, which consists of two 6 MW wind turbine generators located approximately 24 nautical miles off the coast of Virginia Beach. Approving that project, which was estimated to cost approximately $300 million (excluding financing costs), the Commission – noting the high cost per MWh and the risk being placed on ratepayers — expressly found that such approval did not foreclose rejection of future projects (such as the instant one) if the Commission found the project to be imprudent.

Thus, it is instructive that in subsequently enacting legislation for this Project, the General Assembly expressly set forth particular circumstances under which costs for such project must be presumed to be reasonable and prudent.

She calls on the General Assembly to revisit the project, which will take years to build and many more years to pay for, “to determine if additional steps are warranted to reduce the economic burden that will be placed on Dominion’s customers as the Project proceeds.” Perhaps some General Fund cash could be applied, or the proceeds from the “consumer-funded” Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, she suggests.

The order and Jadgmann’s additional comment also focus on how the risk is being placed entirely on captive ratepayers, something else the Assembly could revisit and change, if not for this project, then for any future one. They could insist Dominion do what other states are doing: Letting non-utility firms actually build and own the turbines and sign power purchase deals with utilities.

It will matter. Dominion’s published plans have called for a second, equally large tranche of turbines next door to this project, and the Biden Administration and Congressional Democrats are now placing most of their energy eggs and tax-backed financial incentives in the offshore wind basket.