Publishing a little magazine is attractive to exactly one kind of person: a writer who doesn’t want to work for somebody else’s magazine. The bug got me early on, when I published an “underground” version of my San Diego High School newspaper. That I was also the editor of the official paper only made the underground version more fun—because, it turns out, I don’t even like to work for myself.

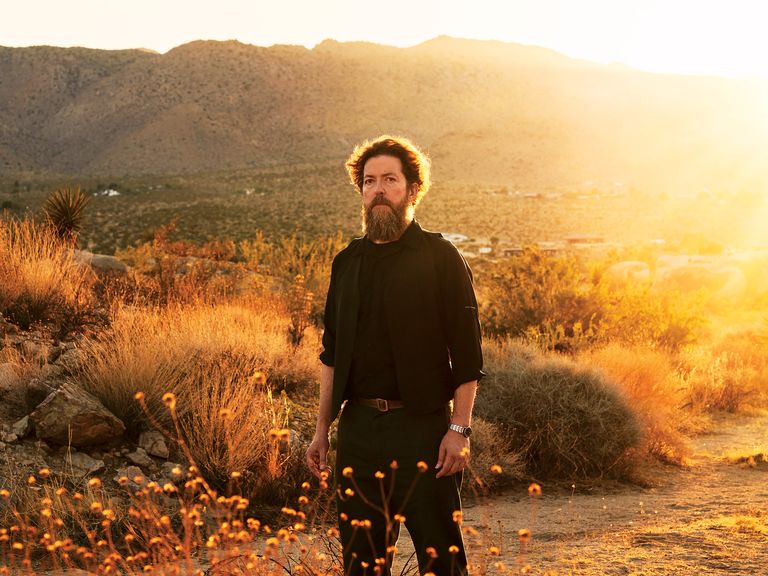

What appealed, then as now, was the solo effort, the sense of mission, the romance of it all. Typing late at night, radio or records playing low, the fireplace roaring, coyotes singing out beyond the back fence. This is all I ever wanted. After four decades in the trade, it shows: 2023 marks the eighth year of Desert Oracle, an occasional publication and weekly radio show that is both burden and joy, but I’m still typing in the night.

There were “real” jobs along the way, all variations on a theme: daily newspaper reporter, wire service editor, magazine writer, radio broadcaster, foreign correspondent, and, most shamefully, “professional blogger”—mostly for websites owned by Gawker Media. I launched independent web titles, too, either alone or with the rare partner who shared the compulsion: L.A. Examiner and Tabloid.net are the only ones remembered by anyone, neither owing to financial success.

But as the digital world consumed ever more of the real world, I dreamed of making something tangible again, something you could hold. Something that would still be there when the computer died, when the network went down, when the inevitable solar storm erased all the hard drives in the world.

There is a Syriac epic poem called “The Hymn of the Pearl,” which shows up more or less complete in the apocryphal New Testament text the Acts of Thomas. The hero is sent to a foreign land to retrieve a prize from a great serpent and deliver it unto God. But this protagonist is led astray and falls into the common life of the population around him, a life of eating and arguing and getting through the day. He utterly forgets his mission, just as David Bowie’s alien-savior character in The Man Who Fell to Earth loses himself to love and television and liquor.

These are epic stories, but they have lessons for mortals, too. A decade ago, writing for a (now dead) blog called the Awl, I remembered my mission. In the never-ending effort to wring “content” from personal history, I’d typed up some columns about the many media jobs that made up a lifetime of editorial labors. One such column was about a rural weekly called the Back Country Trader in Lakeside, California, where I’d spent a little time in the 1980s helping a grizzled and charming editor-publisher named Glenn Hayes on deadline nights. (On publication days, I delivered the newspapers to a dozen little towns and outposts along the mountainous eastern edge of San Diego County.)

This article appears in Issue 22 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

The newsroom was the back half of a narrow commercial space in an Old West–themed retail strip on Lakeside’s main street. Glenn’s office was a cube of 1970s wood-grain paneling with window cutouts on three sides, his desk and typewriter and endless piles of books and binders obscured by great clouds of cigarette smoke. He was lean and good-looking and invariably dressed in an old brown corduroy sports coat over Levi’s and beat cowboy boots. His coffee cup was filled with Bushmills Irish whiskey, the bottle close at hand.

What Glenn did best was talk, telling long, ridiculous stories of local corruption and ineptitude, of botched sheriff’s raids and the occasional big event that grew wilder with every retelling. Now and then he’d cough for a while, and I’d use this pause to ask if his column was done. The typesetter and paste-up person was long gone by this hour, so the hole on the page flats would need to be filled by me, before I left for the night. Glenn Hayes would finally peck out eight column inches of copy and I’d re-peck it into the great blue Linotype machine, and that strip of text would be slapped down. Another week, another small but satisfying victory.

I wasn’t there long. I didn’t even work there, officially. It was my first wife who had the job as the sole reporter there. We lived so far away, up the mountain at Lake Cuyamaca, that I’d hang around the newsroom while she finished her stuff. Once Glenn figured out I could type and do layout, he put me to work. The pay was whatever quarters I got from the far-flung news racks in those little cow towns and semirural exurbs and dots on the map: Alpine, Barrett Junction, Campo, Dulzura, El Cajon, Flinn Springs, Glenview, Harbison Canyon. The reward, beyond the sheer enjoyment of the effort, was the close-up look at a way of life nobody told you about in school. Glenn Hayes had been running small-town newspapers here and there for many years at that point—this one was financed by an ex-girlfriend who was a local real estate agent. It was the “greed is good” decade, which meant working for a lot of creeps, which seemed an awful way to exist. This was the opposite. This was living with purpose.

The paper served an immense area, from the apple orchards of Julian to the ocotillo sand flats along the Mexican border. The people out there were mostly Dust Bowl refugees, living far from civilization in a time before satellite television and the internet homogenized country life. Plenty of these “East County” people didn’t even have telephone service in the rocky canyons and scrub oak valleys where they made their homes. The Back Country Trader connected these settlements with news nobody else bothered to cover, alongside small-town columnists and small-business advertisements. The classifieds were a delight to read, from “free goats” in the livestock section to the plain poetry of the lonely hearts listings.

That’s what I’ll do next, it occurred to me after remembering all this, in 2011. Or last, as my 50th year was approaching.

Why not?

Well, there were plenty of reasons: Newspapers were all but dead, especially the local and small-town variety. Facebook had deliberately targeted the small businesses that kept little newspapers afloat. The national advertising agencies were all about television by the early 2010s, as only local TV stations had survived the media die-off, and mostly because they were owned by national conglomerates.

“News,” in the sense of “what’s going on around me,” requires reporters going to meetings and readers calling in tips and people having no other means to give away excess goats or find love again as a rural widow with too many goats. It requires a perspective formed by a sense of place—something that nearly vanished by 2016 or so, when most “news” became national political gossip.

How to get around all that? My bet was that people still longed for words and images about where they lived, the places they loved. Social media shows how deeply people feel about their local sports or fast-food franchise, how happily they pile on the disdain for a poorly presented version of their hometown.

The place I’ve called home for decades isn’t even a town. It’s a region, the Desert Southwest. Sparsely populated, except for the tourists during the mild seasons. A place dense with stories, if not what you’d call news. I was sick of “news,” anyway. After 40 years in the trade, everything feels like a listless remake of something that happened before. The same events, the same characters, the same attempts at outrage and novelty.

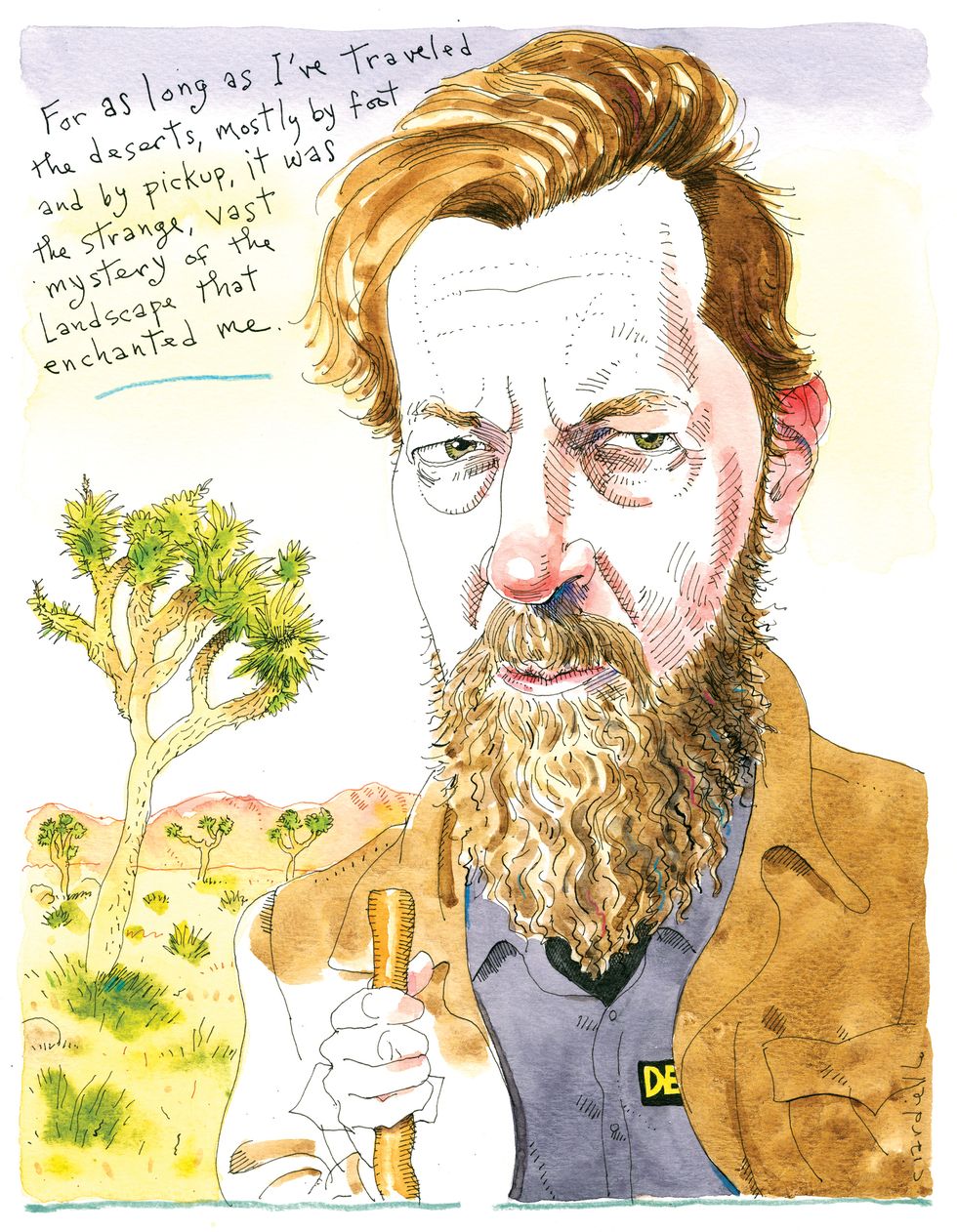

My periodical, which I would name Desert Oracle in honor of the grandly titled newspapers of the gold rush, would tell stories of the place with no concern for timeliness. For as long as I’d traveled the deserts, mostly by foot and by pickup, it had been the strange, vast mystery of the landscape that enchanted me. It was out here, under the endless sky, on land mostly held in public trust by the American government, that a human being could experience the old way of life, the life we all lived for 300,000 years, before climate change and concentrated political power began herding us into settlements some 10,000 years ago.

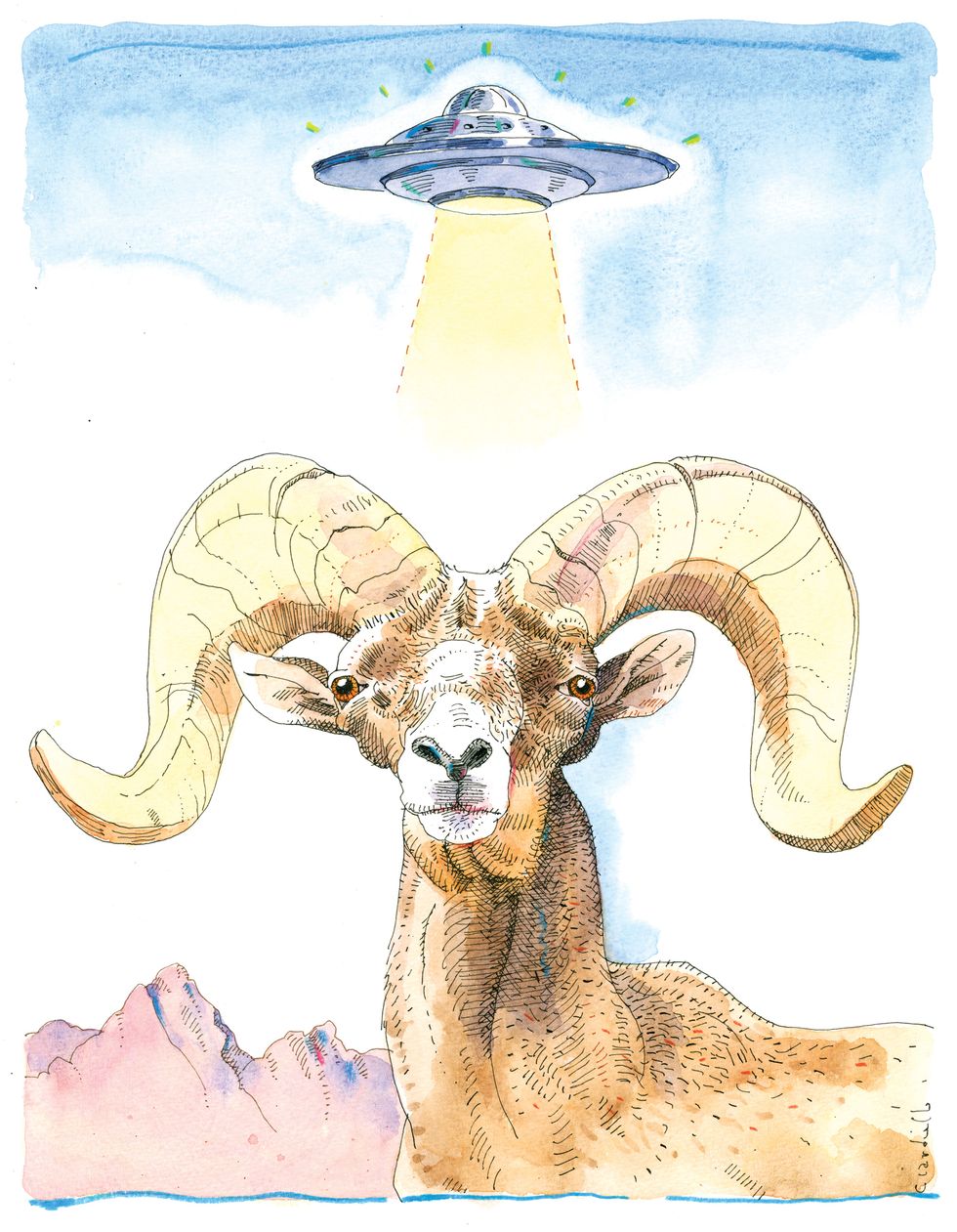

In the eastern Mojave, my favorite place on Earth, a person can set up camp without another human being in sight. Friends and lovers can speak to one another without distraction, without the oppression of phone notifications and email. Wildlife is visible and active: tortoises, desert bighorns, long trains of black-tailed mule deer traveling through the dusk, the brush busy with quail and lizards. People traveled these lands for millennia without making permanent residences, leaving mysterious rock art to mark their routes. Between the Colorado River and the wall of mountains to the west, water was hard to find—no justification for cliff dwellings or Casa Grande–style megastructures. People lived lightly on this land, moving with the seasons. Ask anyone who spends Christmastime in the desert: it’s a paradise as long as you’re not there in summer.

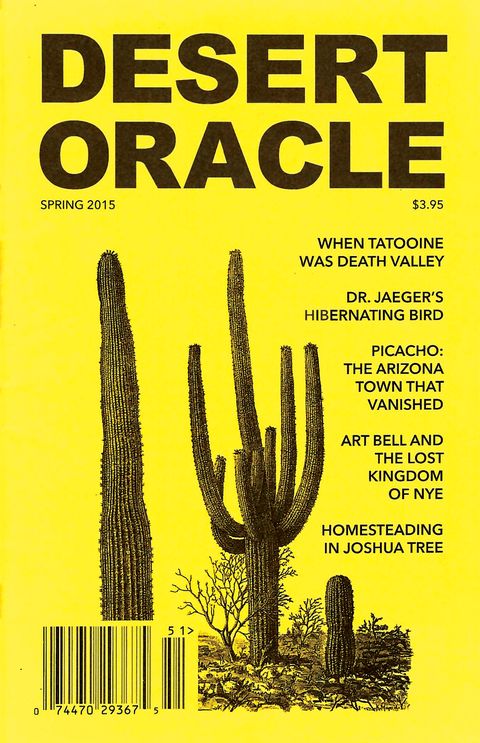

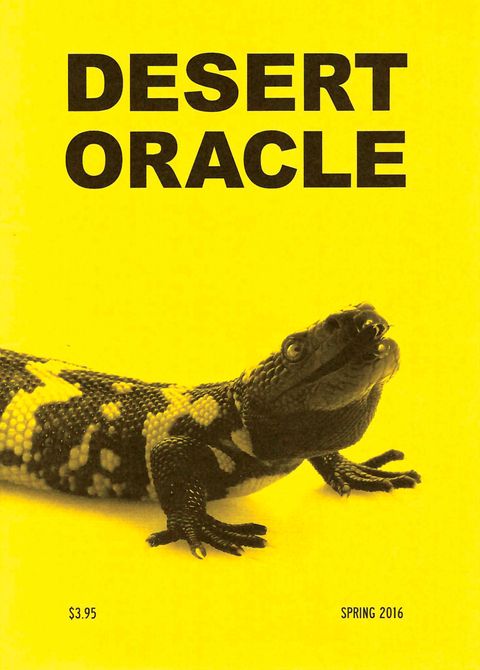

This little publication would be a pocket-size “field guide.” Easy to mail, easy to carry. In honor of the regional-press guidebooks of my youth—Death Valley Jeep Trails, from La Siesta Press in California, was a favorite—the cover would be colored cardstock, yellow like the desert sun. The inside would be clean, only black ink on white pages. Color drenched every screen and piece of printed material; it was overabundant, from the iPhones to the giant TVs to the hideous graphic design churned out for real estate flyers and consumer catalogs. Other than subscription forms and a few teasers on social media, there would be no digital presence, no electronic version. To get a copy of Desert Oracle, you’d have to subscribe by mail order or find an issue in one of the handful of desert shops that agreed to carry it.

The articles would evade the personal-tell-all mode of social media and reality TV and New York Times op-eds by generally doing away with bylines and focusing not on the writer but on the tale, the place, the wonder. (The word “I” has shown up in this remembrance far more often than in nine issues of Desert Oracle.)

Because I’d sold a website in 2012—the political blog Wonkette, given to me by Gawker’s Nick Denton because he couldn’t find a willing buyer—I had just enough money to survive without working another job. The new periodical would have to be a low-budget

operation.

And it would have to create its own infrastructure, as I learned when trying to find regional distribution. The great die-off of magazines was well underway. I found only one distributor remaining in the western half of the country, and the few people there weren’t interested in my eccentric little project. Most of the local printing presses had shut down too, throughout the Southwest. Those that survived did a lot of direct mail and state-government directories.

By necessity, I would serve as primary writer, sole editor, graphic designer, photographer, layout artist, and production manager, as well as being the subscription and shipping departments.

In January 2015, after several months’ work putting together the first issue, Desert Oracle was born. I loaded the full press run of 10,000 into my car and unloaded the cartons in the garage. Now what?

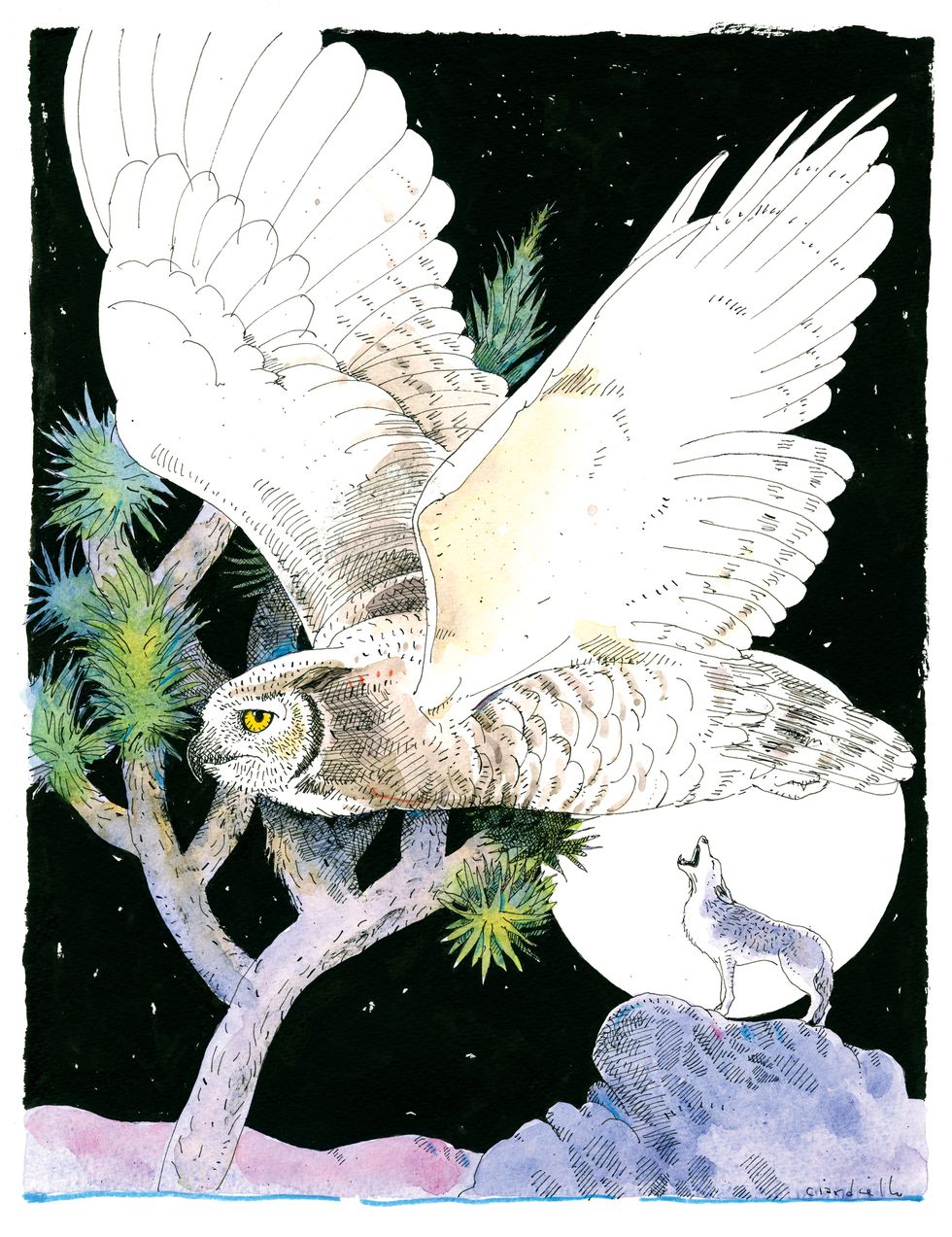

Sometimes you get lucky, and it’s the right moment for whatever you’ve created. My little field guide with the bright yellow cover appeared just as the millennial generation was discovering the beauty and wildness of the Mojave Desert. The usual factors of economics and demographics were involved: With 40 million people in California, only the wealthy could afford beach holidays and second homes. But out in the post–housing collapse wasteland of San Bernardino County, you could still find a gutted 400-square-foot homestead cabin on a couple of acres of creosote and broken glass for $50,000. And it truly was “a magical place,” like the Instagram posts promised: Clear skies, with the Milky Way spilling across at night. The eerie songs of the coyote and the great horned owl. Those strangely beautiful Joshua trees with their many gnarled arms ending in spiked-yucca fists.

A new company, Airbnb, had made the rental of a weekend desert cabin as easy as looking at Twitter. For a generation trapped within expensive little apartments in the coastal cities, space was finally available, at least for the long weekend—whether at the suddenly busy campgrounds of Joshua Tree National Park or in the widely spaced cabins between the park and the Twentynine Palms Marine Corps base. A lot of people were very quickly falling in love with the American desert, as I had in the early 1980s.

One of those young desert lovers, the Los Angeles Times reporter Deborah Netburn, picked up my first issue in Joshua Tree and wrote to me a few days later. She loved the little field guide. Would it ruin it, she wondered, if she wrote a feature article?

During a freezing coal-fog winter in post–Velvet Revolution Prague of the early 1990s, I woke from a vivid dream: It was the Mojave, the High Desert, and I was home—a place I’d never lived, at that point. The house had its own little recording studio. I drove to a diner on the highway to meet a features reporter, who joined me for another long drive as we talked about the desert, dry mountain ranges the color of powdered chocolate all around. It was all very clear, everything but its point.

When the Los Angeles Times reporter contacted me, I recalled that 1992 dream. The interview I’d foreseen would happen in April 2015, and the point was Desert Oracle. More press would follow, because the story functioned as wish fulfillment for many in the media business. After decades of turmoil and collapse and slashed budgets and dumb corporate bosses, the dream of striking out on your own in the Great American West was intoxicating to journalists and editors. And here was this nobody doing it, with no financial backing, no internet content, no “pivot to video.” By the end of that first year, there were more feature articles about Desert Oracle than actual issues of the magazine. Television came calling too, and I found myself getting willingly dicked around by the bottom-feeders of the entertainment industry.

The magazine became a burden as the subscription rolls swelled from a few hundred to 4,000 and ever more shops wanted to carry it and more reporters and photographers wanted to spend an expense-paid couple of days in the now-desirable Mojave following the local oddball—who by 2017 was running the magazine from an especially photogenic midcentury homestead cabin on the side of Highway 62 across from the Joshua Tree Saloon.

I needed fresh distractions and hoped for more income, so I visited local radio station Z107.7 FM and asked for a Friday-night show, inspired and informed by years of late-night back-road drives listening to Art Bell talk about monsters and UFOs on AM radio. Local artist Rohini Walker showed up at the office that same week and asked if I’d do campfire talks at the Ace Hotel in Palm Springs, where she worked booking talent—now I had a performance business, too.

It seemed a good time to hand the magazine off to someone else, because I could not keep up and attempts to hire a managing editor or circulation manager had come to nothing. I emailed the California publishers I knew (including the publisher of Alta Journal, Will Hearst). But there were no takers. A one-person publication is not much without that person. The radio show became a fairly popular podcast, which meant I was back on the internet every week, posting episodes and sharing on social media, the whole draining digital slog. So much for the solitude of the desert hermit.

Like most people, I lost my mind during the pandemic. Still haven’t found it, but humans are nothing if not adaptable. The photogenic office was closed forever during lockdown, and the operation moved back home. Was there a divorce somewhere along the way? Some national tours with the radio show? A hardcover Desert Oracle anthology and bestselling paperback? By early 2022, I’d decided to close the magazine altogether. A new issue hadn’t come out in a year and a half, and every politely emailed query from a long-ignored subscriber was an indictment.

It slowly occurred to me how far I’d drifted from that ideal of Glenn Hayes typing and talking from his paneled office with all the window glass removed—so his words and cigarette smoke could reach the rest of the narrow space—in that Old West–themed commercial strip in Lakeside, California, circa 1987. Glenn always made sure there were interesting people hanging around the newsroom, bundling papers or developing film or typesetting the copy, but mostly adding to the conversation. (Glenn G. Hayes Jr. passed away in 2006, at age 79.)

My rarely published magazine had become a fetish item, as its appearance in hundreds of Airbnb-cabin photos can attest. And I’d become a public oddity, too: What else could explain the New Yorker doing a Talk of the Town about Desert Oracle, complete with a little illustration of the editor-publisher holding that yellow booklet?

When Alta asked me to type up something about running a little magazine—running it into the ground, I mean—it seemed like a good way to say goodbye. Why not write your own obituary?

But something happened, in September 2022. Like the long-distracted hero of “The Hymn of the Pearl” from the Acts of Thomas, I remembered: Right, I’d think to myself, walking the desert trails at sundown with the dog. It’s my duty to put this thing out, to spend deadline nights drinking whiskey and typing up the last bits. It’s part of where I live, it serves a purpose, and there’s nothing to replace it should I give up entirely.

So, by the time you read this, if fate hasn’t decided otherwise, Desert Oracle will live again, back on the quarterly schedule it hasn’t seen since 2016. I’ve hired a managing editor and brought in some new writers, on the strict condition that they spend deadline nights hanging around the newsroom. The 4,065 current subscribers will receive this new beast in their mailboxes with surprise and delight (hopefully). And maybe I’ll not lose sight of the mission, at least for a while.•

Ken Layne publishes Desert Oracle and hosts its companion radio show and podcast from a haunted old compound in the great Mojave Wilderness, one of four American deserts he has called home. He loves all the desert creatures, but especially the local gopher snakes, ravens, coyotes, and antelope ground squirrels. Find out more, if you must, at desertoracle.com.